Reverse Underground Railroad

Synopsis |

The ‘Reverse Underground Railroad’ is the term used for the pre-American Civil War practice of kidnapping free black Americans from free states and transporting them into the slave states for sale as slaves.

Organised gangs of ‘man-stealers’ sought to ‘run-off’ Negroes from the free states and sell them south. These free-booters were known as Kidnappers. The kidnapping of free blacks was a dirty business. Kidnappers physically abused and psychologically terrorized their captives into stating that they were slaves. Many were beaten repeatedly for the attempt to try and claim their free status. This was a large part of the reason that kidnapping accounts were not often told. Once kidnappers sold their victims into slavery, the chances of the person’s free status being revealed were reduced much further. An enslaved free black person’s only chance was to gain the sympathy of a white person who would work to free them. Even then, a slave owner would not be pleased to hear that a newly purchased slave was kidnapped and would often times ignore the facts. Unfortunately when a kidnapping was recognized and taken to trial, the verification of the black’s freedom was extremely hard to prove. Not all blacks carried freedom papers, and those who were kidnapped were often stripped of their papers. On occasion, a judge would not allow freedom papers as evidence on the account that they could be easily forged. The most debilitating factor was that in many places blacks could not testify against whites, leaving families, friends and eyewitnesses out of the courtroom. Only a white person could confirm a black’s freedom. This also presented a problem for those seeking legal recourse. Many whites would be afraid of persecution for helping a black person and sending a fellow white person to jail. Some victims of the reverse underground railroad were kidnapped in the dead of night, stolen from their homes. However, most were probably tricked into boarding a ship as laborers, and delivered into slavery before they knew their fate. |

Principal Kidnappers |

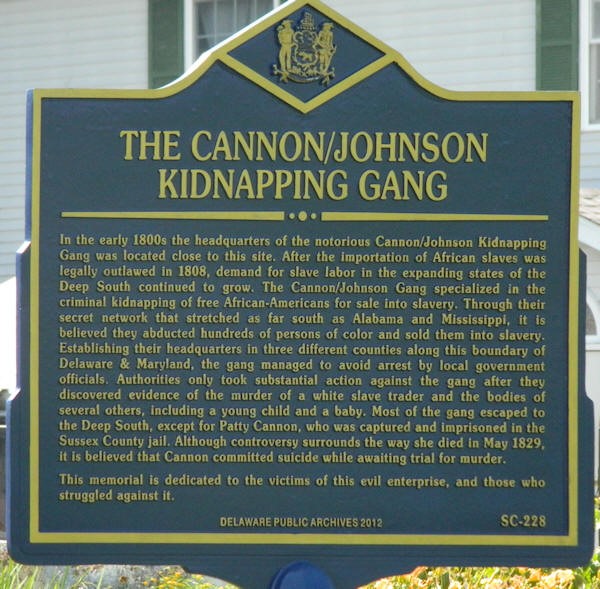

Martha “Patty” Cannon (circa 1760 – 1829)Martha “Patty” Cannon (also referred to as Lucretia P. Cannon) was the leader of a gang in the early 19th century that kidnapped slaves and free blacks from the Delmarva Peninsula and transported and sold them to plantation owners located further south. [The Delmarva Peninsula is occupied by most of Delaware and portions of Maryland and Virginia.] Working from her base at Johnson’s Crossroads in Dorchester County, Maryland, Cannon and her husband Joe Johnson operated a slave trade business preying on African American children from Philadelphia and on African Americans arriving by ship in Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey. Once snared, the gang used a system of station houses to move their prey from freedom to slavery. Victim accounts printed in the abolitionist journal the African Observer state that captives were chained and hidden in the basement, the attic, and secret rooms in the Cannon house. Captives were taken in covered wagons to Cannon’s Ferry (now Woodland Ferry). At the ferry, they would sometimes meet a schooner traveling down the Nanticoke River to the Chesapeake Bay and on to Georgia slave markets. The gang’s activities continued for many years. Local law enforcement officials were reluctant to halt the illegal operations, given the lack of concern that most people in authority felt for negroes in those days, and may have been afraid of the gang’s reputation for violence. When Patty Cannon learned the police were coming, she would slip across state lines away from local police forces. According to depositions from victims who fought their way back to the north, Joe Johnson kept the captives in leg irons. He also “severely whipped” captives who insisted they were free. His wife, Patty’s daughter, was overheard saying that it “did [her] good to see him beat the boys.” (“Boy” was a degrading reference to a black man of any age; Mrs. Johnson was not referring to male children.) A 25-year-old free negress named Lydia Smith testified that she was kept in Cannon’s home before being moved to Johnson’s tavern. There, she was held for five months until she was shipped south with a large lot people being sold into slavery. The gang was initially indicted in May 1822. Joe Johnson was sentenced to the pillory and 39 lashes; records show the sentence was carried out. Cannon and several other gang members, though charged with Johnson, apparently did not go to trial nor receive sentences.

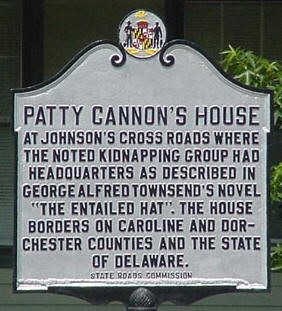

In 1939 the Maryland State Roads Commission erected an historical marker placed at the “Patty Cannon House”, Reliance, Delaware. Research by a PBS history series proved the marker was placed on land Joe Johnson bought in 1821, and that Patty Cannon bought from him in 1826 – but that her actual home was several hundred yards away. Her house, built sometime in the 18th century, was torn down in 1948. The 1939 marker has now had the words “Nearby stood” added. There is however a newer marker: |

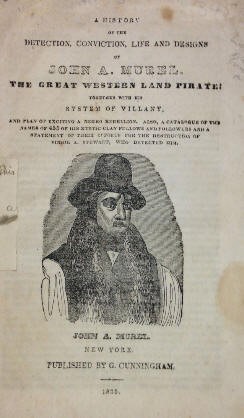

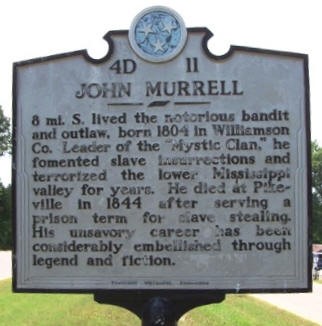

John Andrews Murrell (1806 – 1844)John Andrews Murrell was a notorious bandit, know as a ‘land pirate’ operating along the Mississippi River. As a child Murrell and his brothers were petty thieves, known to have stolen horses and to kidnap slaves and sell them to other slave owners. It was for slave stealing that, in 1834, he was sentenced to 10 years hard labour in the Tennessee State Penitentiary. He died of pulmonary consumption just nine months after leaving prison. The location of his hideout is open to question, however he symbolised Natchez Trace lawlessness in the antibullum period and it’s understandable that his ‘hideouts’ have been said to have been located at most of the well-known areas of particular lawlessness along the Natchez Trace.

Stewart wrote his “confession of John Murrell” under the name “Augustus Q. Walton, Esq.,” for whom he created a biography. Most historians view Stewart’s pamphlet as fictional, since Murrell and his brothers were inept as thieves, having bankrupted their father, who tried to make up for their misdeeds.

The entire episode of the “Murrell Excitement” was inspired by the depraved Virgil Stewart’s imaginary tale. |

|

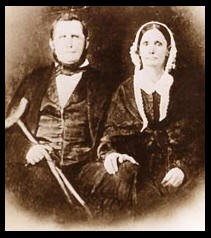

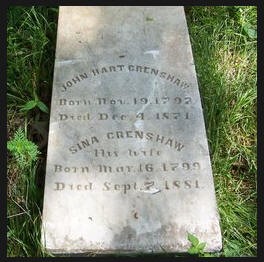

John Hart Crenshaw (1792 – 1871)One of Southern Illinois most famous slavers, and key operator of the reverse underground railroad, was John Hart Crenshaw. Crenshaw grew rich off of the slave trade operating at Shawneetown in the far southern section of Illinois, close to both Missouri and Kentucky. He owned salt mines which were worked by indentured servants, and he made an undisclosed fortune from arranging the kidnapping and sales of free black families. He and his hired men would capture free backs from the North and smuggle them across the Ohio River into Kentucky where the would be ‘sold down the river’ into slavery in the Southern States. In 1834 he had a large, eerily beautiful three story pseudo Greek Revival style mansion built for himself in a Southern Illinois town ironically named “Equality”, some 9 miles west of Shawneetown. “The Old Slave House” (also known as Hickory Hill and Old Crenshaw Place) sits on a small green hill overlooking the Saline River, surrounded by miles of beautiful pasture. The bottom two floors have wooden front balconies and numerous windows, paned with old, wavy glass. The house is filled with antique furniture and the opulence of the era. The second floor contains a large ballroom where guests were entertained. A small narrow hallway leads to the third floor, where suddenly the scenery changes. The walls become bare, and the rooms become cells, including two whipping posts. Slaves were held here, some as house servants, some as breeders, and some as passengers on the reverse underground railroad, doomed to be sold back into slavery”. When the house was built, a secret wagon entrance was constructed in the back of the house. Covered wagons carrying kidnapped blacks and indentured whites would go directly into this entry. Then the kidnapped would be taken up the back stairs to the third floor attic of his home. There they were imprisoned in cells, tortured, raped, whipped, and sometimes murdered. According to local legend, there was also a secret tunnel from the basement to the Saline River so that the kidnapped could be put on boats quickly and inconspicuously. Crenshaw then devised a plan to begin a slave-breeding program in the attic. A slave named Uncle Bob was used as the stud breeder to sire as many slaves as possible to provide Crenshaw with cargo to sell off to the south. A pregnant black woman would bring more money at auction in a slave state. An adult able-bodied slave could bring $400 or more. A child could be sold for around $200. Crenshaw was indicted twice for the kidnapping of black families. The first time was in 1825, and the second was in 1842. It is estimated that Crenshaw stayed in the business of kidnapping for at least 25 years. Crenshaw was one of three defendants in the 1825 kidnapping case. Unfortunately, it is unknown what the outcome of the trial was, let alone the identities of the victims. In 1842 Crenshaw kidnapped Maria Adams and her children, and sold them to a man named Lewis Kuykendall. The prosecutor had to prove that the victims had been taken out of state for the charge of kidnapping to have any legal meaning at the time. Although it was known that Crenshaw kidnapped Maria and her children, it could not be proven that they had left the state. Therefore, Crenshaw and Kuykendall were acquitted.

|

|

Key Reverse UGRR States |

DelawareDetails soon … |

IllinoisKidnapping began very early in the history of the state; and although the legislature commenced as early as 1816 to take measures against it, the practice gradually assumed extensive proportions. The laws concerning the free blacks and the fugitive slaves furnished effective weapons to the kidnappers in their search for their victims. There were two chief centers through which most of the business was carried on. One was near Shawneetown on the Ohio, and the other near Illinoistown, now East St. Louis. From these centers the Negroes were smuggled on the river steamers and carried down the Mississippi to be sold by agents in the South. The profits were large, for one was sure to get at least $100 for an able-bodied slave. To evade the laws against kidnapping, a very neat little scheme was resorted to. The Negroes were conducted from county to county by different relays of men and delivered at the border to non-residents of the state, who saw to their disposition in the South. In this way no citizen of Illinois was directly concerned in taking them out of the state. The Illinois Black Laws of 1819 and 1829 did not do much for the free black population. Both laws alleged that: an African American who migrated to Illinois without certificate of freedom papers was considered a runaway slave and jailed. His or her arrest was advertised for six weeks by the sheriff; and if after one year the uncertified African American could not establish his or her freedom, he or she was indentured for a year. If not claimed during the year, he or she was given a certificate of freedom and considered free unless claimed by an owner in the future. |

|

MarylandDetails soon … |

|

TennesseeDetails soon … |

|

VirginiaDetails soon … |

|

Sources and Further Reading |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reverse_Underground_Railroad

The Myth of a Free State, an exploration of four Illinois counties: http://www.communityinformaticsprojects.org/396/Gallatin/reverseunderground.html McConnel, George Murray, “Illinois and It’s People”, 1902 Wilson, Carol, Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780-1865. Lexington: Univ. Press of Kentucky, 1994. Blackmore, Jacqueline, African American and Race Relations in Gallatin County, Illinois from the 18th century to 1870. Ann Arbor: Proquest, 1996 http://www.everything2.com/title/Reverse+underground+railroad http://agraveinterest.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/old-slave-house-equality-illinois.html Blockson, Charles L., Hipocrene Guide to The Underground Railroad, 1995, Hippocrene Books Inc. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=953 http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=67262 http://allenbrowne.blogspot.co.uk/2014/03/patty-cannon-and-tangent-line.html |