William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown (ca. 1814-1884) was born in Lexington, Kentucky, the son of Elizabeth, a slave woman, and a white relative of his owner. After twenty years in slavery, Brown escaped to freedom in January 1834. He spent the next two years working on a Lake Erie steamboat and running fugitive slaves into Canada. In the summer 1834, he met and married Elizabeth Spooner, a free black woman; they had three daughters, one of whom died shortly after birth. Two years after his marriage, Brown moved to Buffalo, where he began his career in the abolitionist movement by regularly attending meetings of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society, by boarding antislavery lecturers at his home, speaking at local abolitionist gatherings, and by travelling to Cuba and Haiti to investigate emigration possibilities.

William Wells Brown (ca. 1814-1884) was born in Lexington, Kentucky, the son of Elizabeth, a slave woman, and a white relative of his owner. After twenty years in slavery, Brown escaped to freedom in January 1834. He spent the next two years working on a Lake Erie steamboat and running fugitive slaves into Canada. In the summer 1834, he met and married Elizabeth Spooner, a free black woman; they had three daughters, one of whom died shortly after birth. Two years after his marriage, Brown moved to Buffalo, where he began his career in the abolitionist movement by regularly attending meetings of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society, by boarding antislavery lecturers at his home, speaking at local abolitionist gatherings, and by travelling to Cuba and Haiti to investigate emigration possibilities.

Brown’s abolitionist career was marked by a turning point in the summer of 1843 when Buffalo hosted a national antislavery convention and the National Convention of Colored Citizens. Brown attended both meetings, sat on several committees, and became friends with a number of black abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and Charles Lenox Remond. Brown joined these two in their appeal to the power of moral suasion, their rejection of black antislavery violence (particularly the course espoused by Henry Highland Garnet in his “Address to the Slaves”), and their boycott of political abolitionism. Brown’s expanded service to the antislavery movement, his increasing sophistication as a speaker, and his growing reputation in the antislavery community brought an invitation to lecture before the American Anti-Slavery Society at its 1844 annual meeting in New York City; in May 1847, he was hired as a Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society lecture agent. Brown moved to Boston and by the end of the year, he had published the successful Narrative of his life.

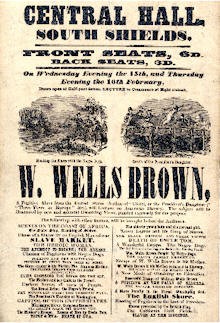

In 1849, he began a lecture tour of Britain and remained abroad until 1854. The length of his stay was conditioned by personal and political motives. He was exhilarated by the tour, had time to write, and enjoyed the benefits of reform circle society. He was also trying to recover from the dissolution of his marriage. Quite as important, once the Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, it was dangerous for the escaped slave to return to America. Concern for Brown’s safety prompted British abolitionists to “purchase” his freedom in 1854.

In 1849, he began a lecture tour of Britain and remained abroad until 1854. The length of his stay was conditioned by personal and political motives. He was exhilarated by the tour, had time to write, and enjoyed the benefits of reform circle society. He was also trying to recover from the dissolution of his marriage. Quite as important, once the Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, it was dangerous for the escaped slave to return to America. Concern for Brown’s safety prompted British abolitionists to “purchase” his freedom in 1854.

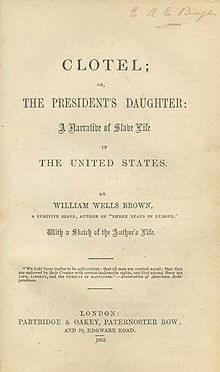

When Brown did return, he had written Clotel, the first novel published by an Afro-American, and was finishing St. Domingo, a work that suggests Brown’s growing antislavery militancy. The publication of those works as well as a travelogue, a play, and a compilation of antislavery songs established his reputation as the most prolific black literary figure of the mid-nineteenth century. During the remainder of his life, Brown lived in the Boston area and produced three major volumes of black history. During the last ten years of his life, he continued to travel, lecture, and write. He completed his last book, My Southern Home: Or, the South and Its People, in 1880.

When Brown did return, he had written Clotel, the first novel published by an Afro-American, and was finishing St. Domingo, a work that suggests Brown’s growing antislavery militancy. The publication of those works as well as a travelogue, a play, and a compilation of antislavery songs established his reputation as the most prolific black literary figure of the mid-nineteenth century. During the remainder of his life, Brown lived in the Boston area and produced three major volumes of black history. During the last ten years of his life, he continued to travel, lecture, and write. He completed his last book, My Southern Home: Or, the South and Its People, in 1880.

Sources and Further Reading:

http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/brownw/bio.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wells_Brown